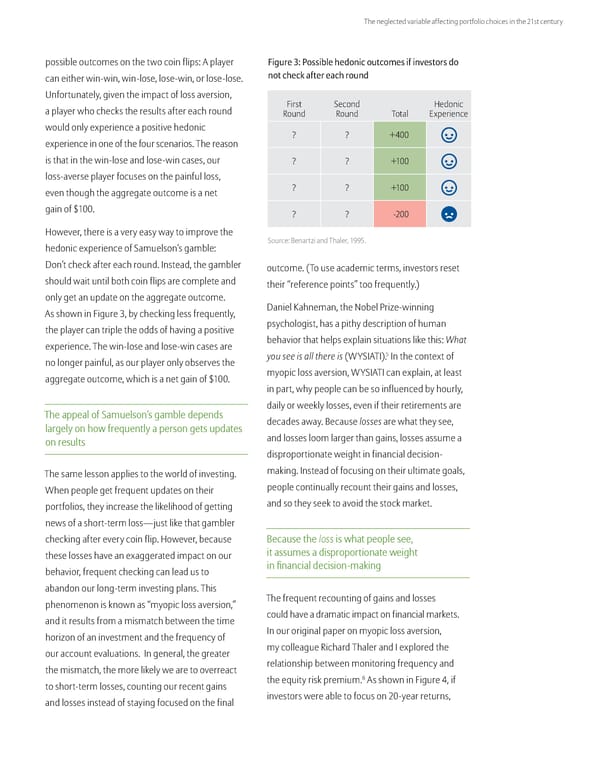

The neglected variable affecting portfolio choices in the 21st century possible outcomes on the two coin flips: A player Figure 3: Possible hedonic outcomes if investors do can either win-win, win-lose, lose-win, or lose-lose. not check after each round Unfortunately, given the impact of loss aversion, a player who checks the results after each round First Second Hedonic Round Round Total Experience would only experience a positive hedonic ? ? +400 experience in one of the four scenarios. The reason is that in the win-lose and lose-win cases, our ? ? +100 loss-averse player focuses on the painful loss, even though the aggregate outcome is a net ? ? +100 gain of $100. ? ? -200 However, there is a very easy way to improve the hedonic experience of Samuelson’s gamble: Source: Benartzi and Thaler, 1995. Don’t check after each round. Instead, the gambler outcome. (To use academic terms, investors reset should wait until both coin flips are complete and their “reference points” too frequently.) only get an update on the aggregate outcome. As shown in Figure 3, by checking less frequently, Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize-winning the player can triple the odds of having a positive psychologist, has a pithy description of human experience. The win-lose and lose-win cases are behavior that helps explain situations like this: What 5 no longer painful, as our player only observes the you see is all there is (WYSIATI). In the context of aggregate outcome, which is a net gain of $100. myopic loss aversion, WYSIATI can explain, at least in part, why people can be so influenced by hourly, The appeal of Samuelson’s gamble depends daily or weekly losses, even if their retirements are largely on how frequently a person gets updates decades away. Because losses are what they see, on results and losses loom larger than gains, losses assume a disproportionate weight in financial decision- The same lesson applies to the world of investing. making. Instead of focusing on their ultimate goals, When people get frequent updates on their people continually recount their gains and losses, portfolios, they increase the likelihood of getting and so they seek to avoid the stock market. news of a short-term loss—just like that gambler checking after every coin flip. However, because Because the loss is what people see, these losses have an exaggerated impact on our it assumes a disproportionate weight behavior, frequent checking can lead us to in financial decision-making abandon our long-term investing plans. This phenomenon is known as “myopic loss aversion,” The frequent recounting of gains and losses and it results from a mismatch between the time could have a dramatic impact on financial markets. horizon of an investment and the frequency of In our original paper on myopic loss aversion, our account evaluations. In general, the greater my colleague Richard Thaler and I explored the the mismatch, the more likely we are to overreact relationship between monitoring frequency and 6 to short-term losses, counting our recent gains the equity risk premium. As shown in Figure 4, if and losses instead of staying focused on the final investors were able to focus on 20-year returns,

The Neglected Variable Affecting Portfolio Choices in the 21st Century Page 3 Page 5

The Neglected Variable Affecting Portfolio Choices in the 21st Century Page 3 Page 5