Econs, Humans, and the Perception of Risk

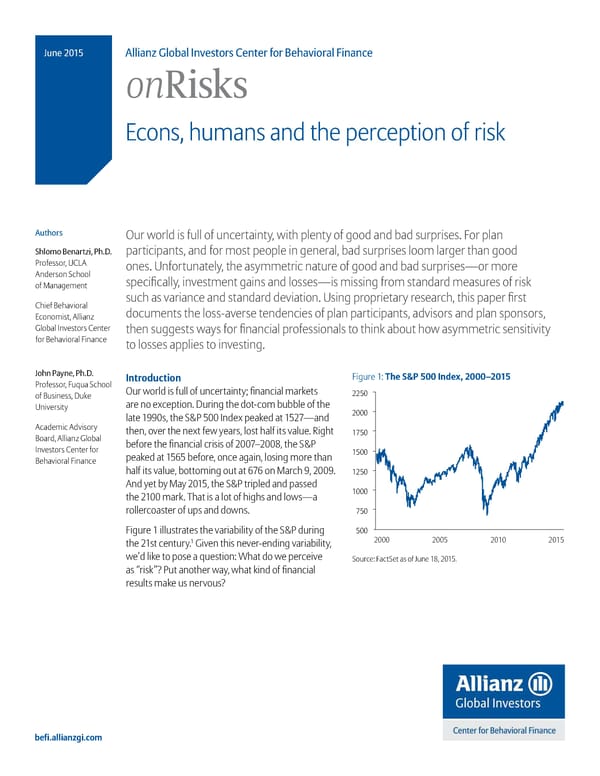

June 2015 Allianz Global Investors Center for Behavioral Finance onRisks Econs, humans and the perception of risk Authors Our world is full of uncertainty, with plenty of good and bad surprises. For plan Shlomo Benartzi, Ph.D. participants, and for most people in general, bad surprises loom larger than good ‚rofessor, Uš›Œ ones. Unfortunately, the asymmetric nature of good and bad surprises—or more Œnderson chool specifically, investment gains and losses—is missing from standard measures of risk of ‹anagement šhief œehavioral such as variance and standard deviation. Using proprietary research, this paper first Economist, Œllianž documents the lossaverse tendencies of plan participants, advisors and plan sponsors, ‘lobal „nvestors šenter then suggests ways for financial professionals to think about how asymmetric sensitivity for œehavioral Finance to losses applies to investing. John Payne, Ph.D. Introduction Figure ” The S&P 500 Index, 2000–2015 ‚rofessor, Fu“ua chool Our world is full of uncertainty financial markets of œusiness, uke 2250 University are no eception. uring the dotcom bubble of the late s, the €‚ ƒ „nde peaked at ƒ…†—and 2000 Œcademic Œdvisory then, over the net few years, lost half its value. ‡ight 1750 œoard, Œllianž ‘lobal before the financial crisis of … †–… ‰, the €‚ „nvestors šenter for peaked at ƒŠƒ before, once again, losing more than 1500 œehavioral Finance half its value, bottoming out at Š†Š on ‹arch , … . 1250 Œnd yet by ‹ay … ƒ, the €‚ tripled and passed 1000 the … mark. Žhat is a lot of highs and lows—a rollercoaster of ups and downs. 750 Figure illustrates the variability of the €‚ during 500 2000 2005 2010 2015 the …st century. ‘iven this neverending variability, we’d like to pose a “uestion” •hat do we perceive ource” Factet as of ™une ‰, … ƒ. as “risk”˜ ‚ut another way, what kind of financial results make us nervous˜ befi.allianzgi.com

Econs, humans and the perception of risk Žo help us žoom in on the psychology of risk, we’d amuelson’s colleague offered the following reason like you to consider two hypothetical investments” for re¥ecting the bet” “„ won’t bet because „ would feel ◾ „nvestment Œ almost always provides a ¡ return the ¤ loss more than the ¤… gain.” „f you also per year, but there is also a small chance of ¡ re¥ected the bet, you probably felt the same way to double your money. For the human mind, losses loom larger than gains. ◾ „nvestment œ almost always provides an ¡ „n their seminal work, ¢obel ›aureate aniel return, but again, there is a small chance of ¦ahneman and his longtime collaborator Œmos ¡ for things to be different, in this case to Žversky estimated that, on average, losses loom lose half your money. § about two to two and a half times larger than gains. ¨„n technical terms, the average “loss aversion Œssuming an investment horižon of one year, which coefficient” is about two to two and a half.© Žhus, investment, Œ or œ, feels riskier to you˜ •e will discuss whenever the upside is “only” twice the downside, this “uestion in detail a bit later, but here’s a “uick as in amuelson’s bet, many people decline the bet.ƒ preview” ‹ost industry measures of risk suggest that „nvestment œ is actually safer than Œ. „n other words, ›osses loom about …–….ƒ times larger than gains— the one that might lead you to lose half your money which could cause people to re¥ect a prospect with is the safer investment. an unusually high return and not much to lose. Žhis paper is about the gap between what “humans” perceive to be risky and how risk is often measured „n principle, there is nothing wrong with being loss by economists, or “econs.”… averse. „t is important, however, that when we navi gate our uncertain world, we take into account our The asymmetric nature of gains and losses asymmetric sensitivity to losses and understand First, though, it’s worth “uickly reviewing some of the how it might impact our choices. academic literature on the nature of risk, which has been the focus of many economists and psycholo Žo highlight the influence of loss aversion, let’s con gists. ‹ore than half a century ago, ¢obel ›aureate sider three pairs of gambles. Žhe three pairs are dis ‚aul amuelson offered one of his ‹„Ž colleagues a played in Figure … ¨see the net page©. Žaking the first £ bet on a coin during lunch. Žhe upside was winning pair as an eample, ‘amble has e“ual chances of ¤… and the downside was losing ¤ . •ould you losing ¤ , breaking even ¨that is, neither winning accept this gamble for real money right now˜ nor losing© and winning ¤ ‘amble … also has e“ual chances of losing ¤£ , breaking even or „f you’re like amuelson’s colleague, you re¥ected the winning ¤£ . bet. „n fact, most people re¥ect the bet. œut why˜ „f you think of it as investing ¤ , then you either get Žhe “uestion, then, is for each of the three pairs in nothing back or ¤£ back, yielding an average win Figure …, would you pick ‘amble or ‘amble …˜ of ¤ƒ . „n terms of rates of return, this “investment” Œlso, which gamble feels riskier˜ provides an epected return of ƒ ¡ in no time, with a worst case scenario that costs about as much as a nice dinner. ‚ut differently, most people re¥ect an investment with an unusually high return and not much to lose.

Econs, humans and the perception of risk Figure …” Would you ic amle 1 or amle 2 Pair I Pair II Pair III ‘amble ‘amble … ‘amble ‘amble … ‘amble ‘amble … ¤ ¤£ ¤ ¤ ¤£ ¤ƒ ¤ ¤ ¤… ¤… ¤… ¤… ¤ ¤£ ¤£ ¤ƒ ¤ ¤ o to read this «ou have an e“ual chance of winning ¤£ , breaking even or losing ¤£ . o to read this «ou have an e“ual chance of winning ¤ , breaking even or losing ¤ . † „f you are an econ, or a trained actuary, then you’d order of the “uestions was randomižed, and we “uickly calculate the epected value and notice that used a typical “attention filter” to ensure participants within each pair the epected value is identical ¨žero were paying attention.‰ for ‚air „ negative ¤… for ‚air „„ and, positive ¤… for ‚air „„„©. Our results indicate that only …§¡ of sub¥ects responded like econs and actuaries and always ince the gambles within each pair have the same preferred ‘amble . imilarly, only £¡ of sub¥ects epected value, you’d then žoom in on the variability always felt that ‘amble is less risky. o what did of each gamble. Œfter all, variability—or, the related our § ¨k© participants prefer and why˜ technical term “variance”—is a traditional measure that financial economists ¨and pension consultants© ‡esults for ‚air „ use to measure risk. Žhe work of ¢obel ›aureate Œs shown in Figure £ ¨see the net page©, starting ¬arry ‹arkowitž on portfolio selection and with our first pair, most preferred ‘amble ¨†£¡©. meanvariance optimižation, for eample, is all about Žhis is not surprising as ‘amble not only has lower minimižing the variability of outcomes for every variability and is therefore attractive to econs, it also Š «ou’ve probably has a smaller potential loss and is therefore psycho given level of epected returns. noticed already that ‘amble … is always more variable logically attractive to loss averse investors. imilarly, than ‘amble . „n particular, the gap between the ¡ of sub¥ects felt that ‘amble is less risky. Žhings, worst and best outcome is ¤Š for ‘amble …, but however, get a lot more interesting as we switch to ¥ust ¤… for ‘amble . Žhus, an econ would always the other two pairs of gambles. prefer ‘amble to ‘amble …—it has the same epected return and it is less risky. ¬owever, if you’re ‡esults for ‚air „„ like most people, then you didn’t always pick ‘amble Žhe second pair is a transformation of the first pair by , or even conclude that ‘amble is less risky. simply deducting ¤… from each prospective out come. ™ohn ‚ayne and colleagues introduced this Žo estimate how most investors feel about the above techni“ue in ‰ and have used it repeatedly since bets, we recently posed the three pairs to an online then in many studies. œy deducting the same sample of § ¨k© participants. Our sample consisted amount from all outcomes, ‘ambles and … still have of Š participants between the ages of £ and Š . the eact same epected value—it is ¥ust negative ¬alf of our sub¥ects were asked to choose between ¤… instead of žero. imilarly, the variability of the the gambles, and the other half were asked to indi two gambles did not change at all—the gap between cate which gamble within each pair felt riskier. Žhe the worst and best outcome is ¤… for ‘amble and

Econs, humans and the perception of risk ¤Š for ‘amble …. •hat, then, has changed˜ ¢ote Œs psychologists would have predicted, § ¨k© partic that the only way now to avoid losses is picking ‘am ipants do not care about theoretical measures of risk ble …, as ‘amble only has negative outcomes. „f our like variance, but are instead driven by the fear of § ¨k© participants are loss averse, then they will now losing. Œs even monkeys know, losses hurt more switch to ‘amble …. Œnd, indeed, the percentage of than gains feel good. sub¥ects choosing ‘amble … more than doubled from …†¡ to ƒ‰¡. imilarly, the percentage of sub¥ects feel § ¨k© participants don’t care about theoretical ing that ‘amble … is less risky has “uadrupled from measures of risk like variance they’re driven by ¡ to §£¡, even though it has greater variability. the fear of losing. ‡esults for ‚air „„„ Žhe third pair is yet another transformation of our €oss a‚ersion and in‚estment decisions first pair, but this time adding ¤… to all outcomes. Žo illustrate the role of loss aversion in investing ¢ote that loss averse investors would now find decisions, let’s reconsider the two hypothetical ‘amble unusually attractive, as there is no way to investments, „nvestment Œ and „nvestment œ, that lose money. Œnd indeed, the percentage of sub¥ects we started this paper with. picking ‘amble ¥umped to ‰…¡, while ‰†¡ felt it is the less risky bet. ¨Œs a “uick reminder, „nvestment Œ almost always provides a ¡ return per year, but there is also a small ummary of results chance of ¡ to double your money. „nvestment œ ›et’s think for a moment about what our § ¨k© almost always provides an ¡ return, but again, participants are telling us about their preferences there is a small chance of ¡ for things to be different, and perceptions of risk. ¬ad they focused on epect in this case to lose half your money.© ed returns and variability, as econs would, they would have always picked ‘amble over ‘amble …. œut „f you are a financial advisor, think about the client you that’s not what happened. ‡ather, their choices have seen most recently. „f you were to invest his or were guided by the desire to avoid the pain of her entire portfolio in either „nvestment Œ or „nvest losing money. ment œ for one year, which one would you choose˜ imilarly, if you are a plan sponsor and were to pick a default portfolio for § ¨k© participants who are Figure £” o lan articiants ercei‚e ris Pair I Pair II Pair III ‘amble ‘amble … ‘amble ‘amble … ‘amble ‘amble … ¤ ¤£ ¤ ¤ ¤£ ¤ƒ ¤ ¤ ¤… ¤… ¤… ¤… ¤ ¤£ ¤£ ¤ƒ ¤ ¤ ‚referred †£¡ …†¡ §…¡ ƒ‰¡ ‰…¡ ‰¡ Felt riskier ¡ ¡ §£¡ ƒ†¡ £¡ ‰†¡ ‚articipants preferred ‚air „’s ƒey finding •hen shown ‚air „„, ‚articipants preferred ‚air ‘amble and viewed it as less participants switched to ‘amble …. „t „„„’s ‘amble and viewed risky” Žhe smaller potential loss provided the only chance to avoid losses it as less risky” Žhere was was psychologically attractive. even though it seemed a bit riskier. no way to lose money.

Econs, humans and the perception of risk automatically enrolled in the plan, would you pick of … individuals managing large corporate plans. „nvestment Œ or „nvestment œ˜ Œgain, ‰ ¡ selected „nvestment Œ and ¡ felt Œ was less risky than œ. „t turns out that if you use traditional measures of risk that focus on variability, the choice is really easy” «ou ¬ow can we reconcile the huge disconnect between should pick œ. •hile it might be a bit counterintuitive, common industry measures of risk and the fact that let’s look at the numbers. ¡ of plan sponsors think „nvestment œ is actually the riskier investment˜ •e recently asked the š„O of Œs shown in Figure §, „nvestment œ has a higher one of the mega plans we interviewed why he felt epected rate of return—it is almost .ƒ¡ ¨ .£¡© „nvestment œ is riskier. ¬is answer was very telling” versus about ¡ for investment Œ ¨.¡©. „n addi “•e don’t define risk in standard deviation terms.” tion, and this is probably the surprising part, „nvest ment œ also has less variability. Žhe numbers are •hen we kept asking what risk is, the š„O thought it clear” Žhe gap between the best and worst outcomes was pretty obvious that risk is about “losing.” Œs a for œ is ¥ust Š¡, but for „nvestment Œ it is actually ¡. behavioral economist ¨hlomo© and a psychologist Žhis means that œ is safer than Œ, at least according ¨™ohn©, we are not surprised that plan sponsors are to calculations based on the variance or standard lossaverse. •e are also lossaverse. deviation of the two investments. œecause œ has a higher return and lower risk, it also has a much higher What to do aout our loss a‚ersion harpe ratio, which means that by most traditional Žhe “uestion, of course, is what should we do about measures œ is simply a superior investment to Œ. our lossaverse tendencies˜ „n the spirit of a publisher that recently asked us to write a book about rewiring „f you use traditional risk measures that focus our brain to cure all our bad money habits ¨in a few on variability, you should pick „nvestment œ. «et, minutes©, should we rewire our brains to eliminate most financial advisors and plan sponsors we loss aversion˜ Obviously not. surveyed picked „nvestment Œ. First, we have no idea how to rewire the brain ¨nor how to write that book©. econd, and more Œnd yet, most financial advisors and plan sponsors importantly, there is nothing fundamentally wrong we surveyed selected „nvestment Œ and felt that œ with being loss averse. œut, and this is a big “but,” was riskier, not safer. „n our sample of advisors, …¡ if we accept loss aversion as part of human nature, selected Œ, and §¡ felt Œ was less risky. Our sample then we have to ensure that our investment strategy of plan sponsors, which is admittedly small, consisted fits how we feel about losses. Figure §” o financial ad‚isors ercei‚e ris Investment A Investment B ›ikely outcome ¨happens ¡ of the time© ¡ ¡ Unlikely outcome ¨happens ¡ of the time© ¡ ƒ ¡ Epected rate of return .¡ .£¡ ‡ange of outcomes ¡ Š¡ tandard deviation . ƒ¡ Š. †¡ harpe ratio . .† „nvestment preferred …¡ ‰¡ „nvestment that felt riskier Š¡ §¡ ource for standard deviation and harpe ratio calculations” risklab.

Econs, humans and the perception of risk „f we accept loss aversion as part of human nature, §. Žo what etent does your approach account for then we have to ensure that our investment strategy differences among individuals and their sensitivity fits how we feel about losses. to loss˜ •hile the median individual has a loss aversion coefficient of about …–….ƒ, there are significant individual differences” ome people Žo help financial advisors, pension consultants are actually not lossaverse and others are and plan sponsors incorporate loss aversion into etremely loss averse. their daytoday activities, we came up with four key “uestions to ask” Summary ›et’s go back to the stock market and the perfor . ¬ow do the limitations of standard deviation and mance of the €‚ ƒ „nde in the …st century. „f harpe ratios factor into your strategy˜ Žhese you are lossaverse, like most humans, then “risk” is measures of variability assume that good and about losing half your portfolio during the dotcom bad surprises are e“ual, but we know that’s crash or the financial crisis of … †… ‰. ¬owever, not the case. ›osses loom larger than gains. you don’t think about the market tripling since its … low as risk. imilarly, we speculate that the …. Žo what etent does your investment strategy founders of Uber, Œirbnb, napchat and Žinder balance loss aversion and gain seeking˜ tandard view their surprising growth and ever increasing deviation is based on the faulty assumption that valuations as success, not risk. gains and losses are e“ual, but “semivariance” makes another faulty assumption that we are Observers often refer to the stock market as a roller … only loss averse and don’t care to seek gains at all. coaster. „t has ups and downs and they are often “uite •e need a more balanced approach to how we surprising. ¬owever, decades of research suggest feel about losses and gains. that people only get scared by the steep falls, not the volatile ups. œut you know what they say” •hat goes £. Œre you assessing the magnitude and likelihood up must come down. ‘iven our lossaverse nature, of potential losses˜ ‚ossible losses should be evaluat we need to think about losses before they occur, and ed prior to making investment decisions, and thus, how we might better manage risks when losses loom before the losses occur. larger than gains.

Econs, humans and the perception of risk nnotes . ource” Factet as of ™une ‰, … ƒ. …. Œ lively discussion of humans versus econs is offered by ‡ichard Žhaler and šass unstein in their book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, «ale University ‚ress, … ‰. £. ‚aul Œ. amuelson. “‡isk and Uncertainty” a Fallacy of ›arge ¢umbers.” Scientia ‰.Š… ¨Š£©” ‰–£. §. ¦ahneman, aniel, and Œmos Žversky. “‚rospect theory” Œn analysis of decision under risk.” Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society §†.… ¨†©” …Š£–…. Žversky, Œmos, and aniel ¦ahneman. “Œdvances in prospect theory” šumulative representation of uncertainty.” Journal of is and ncertainty ƒ.§ ¨…©” …†£…£. ƒ. hlomo œenartži and ‡ichard Žhaler have researched how people react to multiple plays of the amuelson bet, or the stock market, in the following papers” œenartži, hlomo, and ‡ichard ¬. Žhaler. “‹yopic loss aversion and the e“uity premium pužžle.” he uarterly Journal of Economics . ¨ƒ©” †£–…. œenartži, hlomo, and ‡ichard ¬. Žhaler. “‡isk aversion or myopia˜ šhoices in repeated gambles and retirement investments.” anagement Science §ƒ.£ ¨©” £Š§–£‰. Š. ‹arkowitž, ¬arry. “‚ortfolio selection.” he Journal of inance †. ¨ƒ…©” ††–. †. Our analysis is based on the first “uestion each sub¥ect answered, but the results are similar when all three “uestions are included. ‰. O ppenheimer, aniel ‹., Žom ‹eyvis, and ¢icolas avidenko. “„nstructional manipulation checks” etecting satisficing to increase statistical power.” Journal of Eperimental Social €sychology §ƒ.§ ¨… ©” ‰Š†–‰†…. . ‚ayne, ™ohn •., an ™. ›aughhunn, and ‡oy šrum. “Žranslation of gambles and aspiration level effects in risky choice behavior.” ‹anagement cience …Š. ¨‰ ©” £– Š . ‚ayne, ™ohn •., an ™. ›aughhunn, and ‡oy šrum. “¢ote—Further Žests of Œspiration ›evel Effects in ‡isky šhoice œehavior.” anagement Science …†.‰ ¨‰©” ƒ£–ƒ‰. . š hen, ‹. ¦eith, ®enkat ›akshminarayanan, and ›aurie ‡. antos. “¬ow basic are behavioral biases˜ Evidence from capuchin monkey trading behavior.” Journal of €olitical Economy §.£ ¨… Š©” ƒ†–ƒ£†. . harpe, •illiam F. “‹utual fund performance.” Journal of ‚usiness £. ¨ŠŠ©” –£‰. …. ‹arkowitž, ¬arry ‹. €ortfolio selection: efficient diversification of investments„ ®ol. Š. «ale University ‚ress, Š‰.

…out the …llian† loal In‚estors ‡enter for ˆeha‚ioral ‰inance Žhe Œllianž ‘lobal „nvestors šenter for œehavioral Finance is committed to empowering clients to make better financial decisions by offering them actionable insights and practical tools. efiŠallian†giŠcom ©… ƒ. Œllianž ‘lobal „nvestors is an asset management arm of Œllianž E. Žhe šenter is sponsored by Œllianž ‘lobal „nvestors U.. ››š, a registered investment adviser, and Œllianž ‘lobal „nvestors istributors ››š. Œ‘„… ƒ Š…£…ƒ£ƒ ° †££